THE HAGUE. Louis Vuitton has filed its

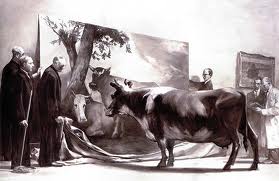

second lawsuit against Dutch artist Nadia Plesner, this time for using an image of the fashion house's Audra bag in her painting

Darfurnica and continuing to display an image of the painting on her website. Although the latest suit can be distinguished from the

2008 suit filed in Paris in that Plesner is not currently using the image for merchandise (in 2008, she used the image on t-shirts and posters with 30% of proceeds going to charity), the use of the image still constitutes copyright infringement because Plesner did not obtain permission prior to its use.

|

| Darfurnica, Nadia Plesner (2010) |

According to New York Magazine, back in 2008, Plesner's failure to respond to the letter sent by Louis Vuitton prompted the company to go to court and seek injunctive relief, not damages (though I suspect that from Plesner's point of view, the latter would have preferable to restrictions on her freedom of expression). At the time, the plaintiff made two valid points: firstly, the need to uphold the rights of fellow artists Marc Jacobs and Takashi Murakami and secondly, the reality (both practical and legal) that if it didn't act to protect intellectual property rights, such rights would be jeopardised in the future. Whether these arguments were at the forefront of their actions is a different matter of course (there's little doubt that LVMH had, and still has, no interest in seeing its handbag portrayed in the context of the Darfur genocide).

The right to freedom of expression (a constitutionally protected right under the First Amendment of the US Constitution and a fundamental human right under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights), is often mistaken for being an absolute right. Rather, it is a qualified right for not all speech is protected (think defamation, fighting words, obscene speech, fraudulent statements...) and the right in respect of that speech which is protected exists not in a vacuum but in a balancing act with other laws such as privacy, consumer protection and copyright, among others. In other words, Plesner's argument that her right to freedom of speech and expression and/or her charitable purposes should (or in fact do) trump any copyright infringement is inaccurate and misplaced. I wonder if what she meant to say is that there is/should be an exception to copyright infringement for artistic expression (as there is under US copyright laws). On the other hand, had she replied to Vuitton's letter in 2008 and requested permission to use the image in 2010 (probably also having to pay a fee for use of the image), each or both instances of litigation may have been avoided. What's clear is that ignoring the problem (and the law) is not the way to go.

UPDATE: for those that have suggested that I myself have engaged in copyright infringement by displaying the image, I would like to point out that I e-mailed the artist herself to request permission to display the image prior to publishing this post (something I do before every posting of an image of a work subject to copyright protection). Likewise, I would like to clarify that the references to privacy, consumer or other rights are merely illustrative -- they are not necessarily limiting the freedom of speech in this case. The intention was to show that the right was not absolute and that legal rights generally are in a constant state of balance and do not exist in insolation from each other.