A Tracey Emin forger has been sentenced to 16 months imprisonment by the Manchester Crown Court for making "at least 11 forgeries" and selling works on eBay for £26,000. Given the nature of some living artists' works today, a forgery of a contemporary work can be easier to create from a technical perspective than say a fake of an Old Master painting, especially since a forger is far more likely to obtain the same materials living or recently deceased artists use than those artists used centuries ago (fakes are often discovered as a result of forensic evidence revealing that the pigments in a painting were not available at the time the artist was supposed to have painted the work -- see link from "gold standard" fakes post). However, from a provenance perspective, it's far riskier to pass off as authentic a work by a living artist than it is for a centuries-old painting whose provenance may be undocumented or incompletely documented.

In this case, the forger not only chose to imitate the work of a critically-acclaimed YBA who is also a highly public figure, he then proceeded to auction the work in the most public manner imaginable! That's not just risky, it's plain stupid. And particularly "distressing" for Emin since the forger learnt his trade working alongside the artist herself in her gallery in London.

Saturday, October 30, 2010

Thursday, October 28, 2010

Eastward bound via Paris and Marrakech

To the East we go! As I've mentioned before, Paris and above all the East (Beijing, Hong Kong, Russia) are the new hotspots in the art world. Not only are the traditional art centers in the West feeling the pressure to compete with their younger Eastern counterparts, a taste for the East has also been palpable in recent auctions with a growing contingent of buyers demanding Chinese art. Below are a few recent links on the emergence and growth of thriving new markets.

- PARIS. France's "premiere" art fair: FIAC. The five best booths according to ARTINFO.

- MARRAKECH. "Morocco is developing economically and will be very important in the Middle East." It only makes sense then that it should get its first art fair in Marrakech.

- DUBAI. Mahmoud Said's 1929 painting sold for $2.5 million at Christie's Dubai, setting a world record for Middle Eastern Art. The modern and contemporary auction netted $14 million, far exceeding the estimate of $6.7 million.

- BEIJING. Poly auctions opens fall season with strong sales of diverse Chinese antiquities.

- SHANGHAI. "Dizzying array of art" at the Shanghai Biennale.

Labels:

art at auction,

Art fairs

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

Warhol authentication and a lesson in litigation strategy

NEW YORK. The U.S. justice system is hardly the breeding ground for David and Goliath-type endings so when Joe Simon went up against the Warhol Foundation and Art Authentication Board all guns blazing, it was only a matter of time before "money, power and legal expertise" dictated the outcome of the litigation. Instead of limiting the complaint to challenging the Board's rejection on two occasions of myandywarhol's authenticity, Simon also sought damages and injunctive relief in federal court "alleging anti-trust violations, collusion and fraud." Despite the abrupt, unsatisfactory ending to the three-year long litigation (not to mention the waste in litigation costs), the case should lead to increased scrutiny of the Warhol Foundation's exercise of its leverage in the market. Technically, the Art Authentication Board's opinion on the authenticity of a work is but one more opinion; however, the reality on the market is vastly different as the major players, including Sotheby's and Christie's, will not sell a purported Warhol without Board authentication. The mere existence of the power to manipulate the entire market for Warhols is not, in and of itself, sufficient to prove the unlawful exploitation of such power. Still, given how prolific Warhol's oeuvre is and the fact that there is more than one collector out there feeling hard done-by the Authentication Board and/or Foundation, this may not be the last time the organization has to retain the services of the preeminent legal minds in the country.

UPDATED: Ouch!

Joe Simon intend to abandon his claims against the Warhol Foundation at the next hearing scheduled for November but counsel for the defendant has made a statement making it clear that the Warhol Foundation will continue to pursue its counterclaim against Joe Simon. According to The Art Law blog, the Foundation's attorneys made the following statement:

"The resources Mr. Simon forced the Foundation to expend litigating against these meritless claims would have otherwise gone to funding its charitable mission of promoting the visual arts and preserving the legacy of Andy Warhol. While Mr. Simon may now prefer not to face Defendants’ legitimate counterclaims, the Warhol Foundation is fully committed to pursuing all its legal rights and claims against Mr. Simon to recover the funds it has been forced to waste and give them back to the charitable causes to which they always belonged."

UPDATED: Ouch!

Joe Simon intend to abandon his claims against the Warhol Foundation at the next hearing scheduled for November but counsel for the defendant has made a statement making it clear that the Warhol Foundation will continue to pursue its counterclaim against Joe Simon. According to The Art Law blog, the Foundation's attorneys made the following statement:

"The resources Mr. Simon forced the Foundation to expend litigating against these meritless claims would have otherwise gone to funding its charitable mission of promoting the visual arts and preserving the legacy of Andy Warhol. While Mr. Simon may now prefer not to face Defendants’ legitimate counterclaims, the Warhol Foundation is fully committed to pursuing all its legal rights and claims against Mr. Simon to recover the funds it has been forced to waste and give them back to the charitable causes to which they always belonged."

UPDATE: the Fisk saga continues

The Tennessee Attorney General filed last Friday a second proposal regarding the future of the Stieglitz collection. Background to and the Chancery Court's rejection of his first proposal can be found here and here (Fisk went on to revise its prospective agreement with the Crystal Bridges Museum in light of the Court's ruling). The AG's latest filing is the product of the establishment of a fund by Fisk alumna Carol Creswell-Betsch that has already received commitments sufficient to "allow Fisk University to keep its Stieglitz art collection and display the works on campus at no cost to the school" (approx. $130,000 a year). Assuming Judge Lyle is still of the view that the winning proposal must secure the long-term financial health of Fisk, I, like Donn Zaretsky of The Art Law Blog, suspect the AG's second proposal will be rejected. However, given Judge Lyle's past record and the ever-illusive notion of "donor intent," of course, who knows what the next installment of Fisk news will bring. Meanwhile, Fisk University has already knocked-down the AG's second proposal.

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Blair Di Donna gallery to open in uptown New York

NEW YORK. For those active or interested in the secondary market, former Sotheby's vice chair Emmanuel Di Donna is joining forces with London dealer Harry Blain to open the Blair di Donna gallery. The venture represents the teaming up of two artworld moguls -- Di Donna was with Sotheby's in New York for 17 years and Blain co-founded the London galleries Haunch of Venison (bought by Christie's in 2002) and very recently, Blain Southern (focused exclusively on the primary market and set to open in New York after closing its doors in Berlin). The Blair di Donna gallery is due to start trading next month and "the ambition is to have the doors open, and the first exhibition up, in time for the New York auctions in May." Keep you posted (no pun intended).

Labels:

New York,

secondary market

Insurer v. Insured

Donn Zaretsky of The Art Law Blog points us in the direction of an insurance case about which party, the insurer or the insured, should get a stolen artwork when it's recovered years after the insurer made a payment in the amount of the policy's limit. Since in this particular instance the valid and enforceable written agreement governing the relationship between the parties had a "plain and unambiguous" provision directly on point, the resolution of the dispute turned out to be a straightforward application of basic contract law principles. Now the really interesting question is in favor of whom would the Massachusetts court have ruled had there been no contractual provision determining who gets what in the unlikely situation that a stolen artwork paid for under an insurance policy is found decades later.

UK public funding for the arts cut by almost 30%. "Can, and will, British collectors make up the shortfall?"

LONDON. As many had been fearfully anticipating for months, yesterday the British government announced that Arts Council England ("ACE") - "which distributes money to hundreds of arts venues, theatre groups and galleries" - is to have its budget cut by 29.6% (representing a £100 million cut in funds by 2014). National museums will take a 15% cut over the next four years assuming the ACE complies with the government's request that it limit cuts to "arts organisations" up to this amount. The government is alleged to have said that funding of the arts should follow in the steps of the US model and make up the cuts in public funding by increased private giving. What the government has thus far failed to do is introduce the tax incentives upon which the US model is predicated. US institutions are able to "survive" (an increasingly debatable statement) on private donations not because the system or society successfully encourage altruisim but because they reward it financially. The former Tate Britain director, Stephen Deuchar, said he knew of "certain donors [in Britain] who are just waiting for this to happen." As Boris Johnson, the Mayor of London, put it speaking at Frieze: "we need to be incentivised to give."

So what US tax incentives are British collectors waiting for then? There are several tax benefits for the private philanthropist making a charitable donation to a tax-exempt organization in the US (one falling under any of the tax-exempt categories in IRS 501(c)(3), (4), (6) or (19)). The most important of these is the immediate federal income tax deduction the donor gets when he itemizes the charitable donation in his tax return (the other two main forms of tax relief are the avoidance of capital gains tax on appreciated assets and an estate and gift tax deduction). The amount deductible depends on whether the donated art constitutes capital gain property or ordinary income property. If the artwork donated was owned for a minimum of 12 months and during this time it appreciated in value, it falls within the category of capital assets referred to as capital gain property and the donor can deduct the full fair market value ("FMV") of the donation on the date of the contribution subject to certain rules and conditions (including the requirement to file an appraisal in support of the deduction if the FMV is greater than $5,000). This means that a taxpayer can actually gain an advantage if he donates capital gain property obtained at a discount to the FMV. If, on the other hand, the artwork does not constitute capital gain property either because it was owned for less than a year prior to the contribution or it did not appreciate in value, it will constitute ordinary income property and the donor can only deduct his/her investment in the art (i.e. the cost of purchasing the art). In addition, the amount of the deduction in any individual tax year may be limited.

According to The Art Newspaper, "in Britain you get most tax breaks from the grave: the Acceptance in Lieu system reduces death duties by the value of the work of art donated. When alive, people who give over £25,000 a year (or £150,000 in six years) earn a tax deduction of 25% under the Gift Aid scheme, but if they give a work of art, they get nothing." Then there's the issue of public awareness of any existing tax advantages. Having lived in the US now for just over two years, I strongly agree with the article's statement that "tax incentives are known to everybody" in the US. This is true of people of all ages and backgrounds, personal and professional. However, the lack of knowledge in the UK should be a relatively minor concern because not only is it fairly easy to correct, it's also going to be the case that the donors who are likely to make the most meaningful donations (in quantitative if not also qualitative terms) will be well-versed on the subject and if not, their tax advisers will be.

Despite the case for incentivizing private giving through tax reforms in the UK being stronger than ever, I want to take this opportunity to draw attention to the often overlooked problem of institutions accepting excessively restricted private donations. Gifts, more often than not, come with strings attached. Museums, generally heavily biased towards collection-building, accept donations to hold on trust for the public only to find decades later that it is the donor who controls the artwork from his/her grave for the indefinite future. While I don't want to discourage private funding of institutions and I'm aware of and sensitive to the recent financial struggles of many institutions, in the US and the UK, in my opinion, a museum must retain a certain amount of flexibility in art collecting and should reject a donation if it reasonably foresees difficulties in the future in giving effect to the donor's intent. But most importantly, it is donors who must refrain from tying-up the art they donate. Gifts should be made outright, free from vague or cumbersome conditions that can, and often do, result in expensive litigation for the recipient institution. The UK should undoubtedly incentivize private funding of institutions to avoid the announced public funding cuts materializing into "redundancies, fewer exhibitions and programmes, reduced opening hours and smaller acquisition budgets." On the other hand, it is imperative that they consider the particular costs associated with private vs. public funding (I assume English trust law is as donor-friendly as common law in the US and NY State's recently enacted version of UPMIFA).

So what US tax incentives are British collectors waiting for then? There are several tax benefits for the private philanthropist making a charitable donation to a tax-exempt organization in the US (one falling under any of the tax-exempt categories in IRS 501(c)(3), (4), (6) or (19)). The most important of these is the immediate federal income tax deduction the donor gets when he itemizes the charitable donation in his tax return (the other two main forms of tax relief are the avoidance of capital gains tax on appreciated assets and an estate and gift tax deduction). The amount deductible depends on whether the donated art constitutes capital gain property or ordinary income property. If the artwork donated was owned for a minimum of 12 months and during this time it appreciated in value, it falls within the category of capital assets referred to as capital gain property and the donor can deduct the full fair market value ("FMV") of the donation on the date of the contribution subject to certain rules and conditions (including the requirement to file an appraisal in support of the deduction if the FMV is greater than $5,000). This means that a taxpayer can actually gain an advantage if he donates capital gain property obtained at a discount to the FMV. If, on the other hand, the artwork does not constitute capital gain property either because it was owned for less than a year prior to the contribution or it did not appreciate in value, it will constitute ordinary income property and the donor can only deduct his/her investment in the art (i.e. the cost of purchasing the art). In addition, the amount of the deduction in any individual tax year may be limited.

According to The Art Newspaper, "in Britain you get most tax breaks from the grave: the Acceptance in Lieu system reduces death duties by the value of the work of art donated. When alive, people who give over £25,000 a year (or £150,000 in six years) earn a tax deduction of 25% under the Gift Aid scheme, but if they give a work of art, they get nothing." Then there's the issue of public awareness of any existing tax advantages. Having lived in the US now for just over two years, I strongly agree with the article's statement that "tax incentives are known to everybody" in the US. This is true of people of all ages and backgrounds, personal and professional. However, the lack of knowledge in the UK should be a relatively minor concern because not only is it fairly easy to correct, it's also going to be the case that the donors who are likely to make the most meaningful donations (in quantitative if not also qualitative terms) will be well-versed on the subject and if not, their tax advisers will be.

Despite the case for incentivizing private giving through tax reforms in the UK being stronger than ever, I want to take this opportunity to draw attention to the often overlooked problem of institutions accepting excessively restricted private donations. Gifts, more often than not, come with strings attached. Museums, generally heavily biased towards collection-building, accept donations to hold on trust for the public only to find decades later that it is the donor who controls the artwork from his/her grave for the indefinite future. While I don't want to discourage private funding of institutions and I'm aware of and sensitive to the recent financial struggles of many institutions, in the US and the UK, in my opinion, a museum must retain a certain amount of flexibility in art collecting and should reject a donation if it reasonably foresees difficulties in the future in giving effect to the donor's intent. But most importantly, it is donors who must refrain from tying-up the art they donate. Gifts should be made outright, free from vague or cumbersome conditions that can, and often do, result in expensive litigation for the recipient institution. The UK should undoubtedly incentivize private funding of institutions to avoid the announced public funding cuts materializing into "redundancies, fewer exhibitions and programmes, reduced opening hours and smaller acquisition budgets." On the other hand, it is imperative that they consider the particular costs associated with private vs. public funding (I assume English trust law is as donor-friendly as common law in the US and NY State's recently enacted version of UPMIFA).

Labels:

charitable donations,

donor intent,

Taxation

Semantics

What's the difference between a "fake" and a "copy"? And what about an "exhibition-related copy" and an "exhibition copy"? A story on the Warhol Authentication Board's recent report on Hultén’s Warhol Brillo boxes may shed some light. Personally, I'm still a little confused.

Over 10% of "gold standard" forgeries of 20th century paintings went through Christie's

More than 30 paintings collectively worth an estimated £30 million were recently found to be forgeries of major 20th century artworks. Unsurprisingly, the forger's strategy is believed to have been "to create compositions that would relate to titles of documented works whose whereabouts are not currently known." Experts described the forgeries as "gold standard" but some of the works' inauthenticity possibly could and should have been discovered by the leading dealers and auction houses that sold them -- especially since a painting's provenance or history can apparently be discerned from labels or drawings on the back of it. For example, one of the four forgeries auctioned by Christie's had a fake label for "Flechtheim Collection" and it was this very label that aroused suspicions. I don't doubt how seriously the major auctions houses take issues of authenticity and provenance but it seems to me that failing to detect a fake label is hard to excuse and not comparable to not undertaking the (hugely expensive) expert scientific analysis prior to auctioning a painting (plus, I can imagine that having an expert do so is a double-edged sword because you can inadvertently taint a work that was authentic to begin with).

Labels:

Authenticity,

Christie's

Sunday, October 17, 2010

FRIEZING LINKS

LONDON. Another year, another Frieze Art Fair... and so much to cover! Here's a selection of the best links on the fair.

- If you couldn't be there, here's the next best thing: Sotheby's Frieze Week Video Project and the Frieze site itself.

- “People come to London in October to find new artists, and that should be in the auction rooms as well as at Frieze."

- "Is art in some kind of reactionary, recessionary funk?," asks Art Salon.

- ARTINFO's rating of the best and worst booths. Predictably, all the site had to see in blue-chip works were $ signs. I'm so tired of primary market snobs thinking that blue-chips aren't worthy of a critique on the merits. The site's more interesting articles are here and here.

- "Frieze News in Brief" and "Solid Sales at Frieze" both from The Art Newspaper.

- The fair's hipster grass-roots section known as "Frame." Although this year saw a brand new satellite fair called "Sunday" for emerging galleries that don't make it into Frame, according to ARTINFO, Frame "remains the place for young galleries to flourish." Still, the stakes for participating in Sunday are not high ($1,600) when compared to the costs of a booth in Frame ($8,000), itself a fraction of an ordinary booth in Frieze. Overall, "the consensus among those attending was that Sunday was a worthwhile addition to the many events going on during Frieze week."

- The big fish and the fresh cash were Asian and Eastern European. Surprised? Hardly.

The estate tax's return explained

Art collections = estate planning = estate taxes... state AND now federal again?

The anticipated return of federal estate taxes- repealed as part of the Bush tax cuts of 2001- will affect many art lovers, and not in a good way. I would go into it in more detail but Forbes and Professor Bainbridge do a great job and offers some useful tips on how to minimize the impact of the dreaded return of this painful tax. NB- I could be wrong but shouldn't any and all trusts set-up always be irrevocable to avoid federal estate taxes?

The anticipated return of federal estate taxes- repealed as part of the Bush tax cuts of 2001- will affect many art lovers, and not in a good way. I would go into it in more detail but Forbes and Professor Bainbridge do a great job and offers some useful tips on how to minimize the impact of the dreaded return of this painful tax. NB- I could be wrong but shouldn't any and all trusts set-up always be irrevocable to avoid federal estate taxes?

Marion True, the scapegoat...

We will never know whether Marion True knowingly "acquired" or conspired to "traffic in" looted antiquities now that a court in Rome has ruled that the statute of limitations on the two criminal charges brought against the longtime curator had expired. The trial had continued on-and-off for five years during which time the prosecution presented its arguments to the court and called witnesses "who, according to Italian court procedure, were rarely subject to cross-examination." This, together with the fact that the defense never made its case nor did the court ever reach a verdict, means it's virtually impossible to draw any solid, substantiated conclusions with respect to the defendant and the specific allegations made against her. Furthermore, whatever limited conclusions can be drawn these have to be at least partially discounted given the politicization of the proceedings as a result of the Italian government's purported use of the True trial as a platform for its efforts to reclaim antiquities from major American museums. I say "purported use" because my understanding was always that the claims made by the Italian authorities had actually largely been "ethical" rather than "legal" but that the distinction had proven irrelevant in practice because US institutions perceived the claims as legal due to the hugely incriminating evidence found at the Geneva warehouse of Giacomo de Medici (convicted antiquities smuggler and alleged associate of Robert Hecht, Marion True's co-defendant and the dealer she transacted with). Marion True herself discusses, among other things, the "gigantic effect" the trial had on American museums, including the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Metropolitan and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, in an interview she gave The New Yorker on her "trial and ordeal."

Yet despite no verdict and no airing of the defense, the significance of the case cannot be overstated: it marks the culmination of decades of (unethical, if not illegal) acquisitions by museums (dealers and collectors too) of antiquities of unknown or dubious provenance. It's long been the case that market participants have simultaneously acknowledged the prevalence of looted antiquities in the market while routinely dealing in ancient artifacts that lack adequate provenance and denying the causal link between market demand and the growing profit-making business of looting (evidence of the causal link is practically conclusive). The True trial illustrates this intolerable reality perfectly - the pervasiveness of appallingly low standards in acquisitions of antiquities has been such in the last 20 years that either Marion True thought she could get away with it or even a curator of her knowledge and experience (she served as curator of antiquities at the Getty from 1986 to 2005) could not distinguish between an insufficiently documented antiquity and an illicit one. As the director of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, Maxwell L. Anderson, said, Marion True was being indicted "for what was a practice of American museums."

That a single curator has had to "carry the burden" for the practices of a board of trustees that was fully aware of the risks the acquisitions entailed and approved them nonetheless only to condone them later is undoubtedly unfair, not to mention the fact that the charges were anomalous from the outset since as a curator, True was never the recipient of the objects in dispute- the objects were acquired by the board of trustees on behalf of the Getty museum. However, I want to tell Marion True that her five year-ordeal was not completely in vain. Yes the costs of the litigation were exceedingly high- the personal costs to the defendant as well as the costs associated with the intimidation of American museums by the Italian authorities and the less-than-favorable agreements that resulted- but there were benefits too. In 2008, for example, the Association of Art Museum Directors adopted stricter guidelines for acquisitions of antiquities and, above all, the trial has served as a deafeningly loud "wake-up call" to museums in the US (and, ehem, around the world) that BUYING UNDOCUMENTED OR INSUFFICIENTLY DOCUMENTED ANTIQUITIES HAS GOT TO STOP.

Labels:

Antiquities,

provenance

Thursday, October 14, 2010

UPDATE: latest Fisk court filing

The New York Times has reported that Fisk University has revised the terms of the agreement with the Crystal Bridges Museum in relation to the Stieglitz Collection to address some of the concerns voiced by the Chancery Court in Nashville, Tennessee. Notably, "Fisk and Crystal Bridges have agreed that the art will remain at Fisk, in Nashville, until 2013, then be exhibited at Crystal Bridges for two years and returned to Fisk between 2015 and 2017. After that, the art will be on a two-year rotation unless the committee established to oversee the art “has a good reason to make a change,” the university said." A case example of how "the future will be shared," as the opinion section of The Art Newspaper so eloquently put it recently.

For background on the ongoing Fisk litigation see here, here and here. For a good analysis of the latest Fisk news see Donn Zaretsky's commentary on The Art Law Blog, which also includes a link to Fisk's court filing.

For background on the ongoing Fisk litigation see here, here and here. For a good analysis of the latest Fisk news see Donn Zaretsky's commentary on The Art Law Blog, which also includes a link to Fisk's court filing.

Labels:

cy-près,

donor intent,

Fisk

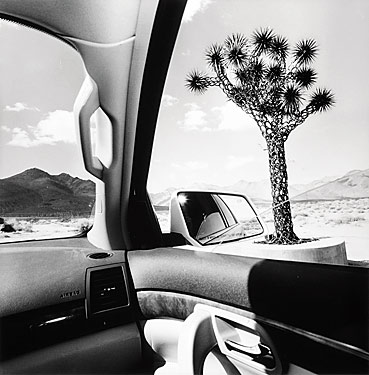

ART PICK OF THE MONTH (Oct. '10)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Through November 28, 2010

The 192 photographs on display at the Whitney represent a visual narration of Lee Friedlander's travels across America over the last 15 years. At first, the images captured from the artist's rented car are so familiar to the viewer that he/she can't help but wonder whether they are worthy of any artistic value being attributed to them. I suspect the sentiment is underscored by many a viewer's cynical take on what gets passed off as "art" today and a somewhat enduring, albeit old-fashioned, belief that the medium of photography is inferior to painting or sculpture due to its accessibility to the non-artist layman.

While the content matter is, in my opinion, hardly new or exceptional (Americana all over again- Coca Cola signs, Joshua trees, billboards, the car itself...), the composition and lighting of the photos in no way resemble the arbitrariness of casual snapshots. Upon closer inspection, it's clear that a lot of thought went into the way in which the structures of the car (both inside and out) frame the landscape and its constituent objects, at times not merely capturing it but actually redefining it. The elements of the car become architectural structures within certain photographs- solid and stoical, embodying linear or curvilinear lines of some definite and purposeful design, magistral.... Likewise, the juxtaposition of different textures and intensities of light is thoughtful, subtle and highly effective in creating two clearly distinct worlds: the inside of the car and the world outside it.

Meanwhile, the curating of the exhibition, which was done in accordance with the artist's specific instructions, is spot on. The photographs are densely hung across the six walls of two small adjacent rooms in order to re-create the sensory overload associated with traveling in a car in America. And it works- the viewer feels overwhelmed by the vast number of images surrounding him in the tight, cramped space and, just like a car passenger, tries to take it all in as best he/she can. This way of displaying photographs reminded me of Julian Schnabel's curating of Dennis Hopper's retrospective at MOCA in Los Angeles last month except because the space was far smaller at the Whitney, the effect was quite different (as was the view of the photos- much better- given the size of the walls).

Definitely a worthwile trip to the Whitney though probably best combined with another exibit/ purpose for the visit as it doesn't take long to view the two rooms.

Through November 28, 2010

The 192 photographs on display at the Whitney represent a visual narration of Lee Friedlander's travels across America over the last 15 years. At first, the images captured from the artist's rented car are so familiar to the viewer that he/she can't help but wonder whether they are worthy of any artistic value being attributed to them. I suspect the sentiment is underscored by many a viewer's cynical take on what gets passed off as "art" today and a somewhat enduring, albeit old-fashioned, belief that the medium of photography is inferior to painting or sculpture due to its accessibility to the non-artist layman.

While the content matter is, in my opinion, hardly new or exceptional (Americana all over again- Coca Cola signs, Joshua trees, billboards, the car itself...), the composition and lighting of the photos in no way resemble the arbitrariness of casual snapshots. Upon closer inspection, it's clear that a lot of thought went into the way in which the structures of the car (both inside and out) frame the landscape and its constituent objects, at times not merely capturing it but actually redefining it. The elements of the car become architectural structures within certain photographs- solid and stoical, embodying linear or curvilinear lines of some definite and purposeful design, magistral.... Likewise, the juxtaposition of different textures and intensities of light is thoughtful, subtle and highly effective in creating two clearly distinct worlds: the inside of the car and the world outside it.

Meanwhile, the curating of the exhibition, which was done in accordance with the artist's specific instructions, is spot on. The photographs are densely hung across the six walls of two small adjacent rooms in order to re-create the sensory overload associated with traveling in a car in America. And it works- the viewer feels overwhelmed by the vast number of images surrounding him in the tight, cramped space and, just like a car passenger, tries to take it all in as best he/she can. This way of displaying photographs reminded me of Julian Schnabel's curating of Dennis Hopper's retrospective at MOCA in Los Angeles last month except because the space was far smaller at the Whitney, the effect was quite different (as was the view of the photos- much better- given the size of the walls).

Definitely a worthwile trip to the Whitney though probably best combined with another exibit/ purpose for the visit as it doesn't take long to view the two rooms.

Sunday, October 10, 2010

Who says lawyers are always the bad guys?!

Finally- a story that may actually give lawyers a good name! Randol Schoenberg, President of the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust ("the oldest Holocaust museum in the US") and the lawyer who represented Maria Altmann in the much-publicized arbitration to recover her family's Nazi-looted Klimt paintings, has donated part of the fees he earned in the Altmann case to fund about a third of the museum's $18 million relocation and expansion costs. Read all about it here.

Bacon cricketer painting to go on sale Nov. 9 in New York

The 1985 painting "Figure in Movement" gifted by Bacon to his friend and doctor, Dr. Paul Brass, goes on sale November 9 at Sotheby's in New York. This is the first time the painting enters the market and it's estimated to sell for $7 to $10 million. The painting is quite special in a number of ways: it depicts a subject matter, cricket, which "fascinated" Bacon and the body and face of the cricketer are inspired by two of the painter's closest companions, also patients of Dr. Brass. The market always likes a good story so I wouldn't be surprised if the painting reaches or even surpasses the high estimate. Read all about the painting's unique story here.

Labels:

art at auction,

Sotheby's

Friday, October 08, 2010

Love a painting but strapped for cash? Try the photo-approach to obtaining art on the cheap (caveat: in most cases, it's ILLEGAL)

I am simultaneously annoyed and bemused when I see people taking photos of art displayed in a museum, artwork after artwork after artwork. I get annoyed because their main concern is digitally recording the fact that they were in the physical presence of the art rather than actually observing, absorbing and hopefully engaging with the art and because it ruins the experience for the rest of us. (At that moment, I'm often reminded of those travelers feverently focused on getting that Great Wall of China or Sydney Opera House snapshot just to mentally tick-off "China" and "Australia" from their cultural to-do lists). Then I wonder, somewhat confused, what it is these frenzied art paparazzi do with the photos afterwards. I picture them showing their encyclopedic catalogue of photos to friends and family shortly before stashing the camera and/or photo album away in the bottom of a drawer and long-forgetting about the art they went to see but never really saw. It had never occurred to me, however, that someone would think about blowing-up one of said photos and hanging it up on their wall though that is precisely what a freelance journalist envisioned (she never went through with it) as she revealed in a recent article in The New York Times.

Her main concern regarding the photo-approach to obtaining "art" for interior design purposes was ethical; what prompted her to write the article was whether it was in fact legal. After consulting various lawyers and law professors, it transpired that in most cases, it's illegal to photograph works of art, even if the reproduction is for your own private use only or the photo is a reproduction of a reproduction. In the US, if a work of art was created before 1923, it's considered to be in the public domain which means you can photograph it without violating any copyright laws. "But if the work of art is more recent, the artist generally has the exclusive right to any reproduction, and the piece is generally covered by copyright law," (my emphasis added). The statement that artworks created after 1923 are generally protected by copyright is a gross generalization and the key date is not one -1923- but several: 1978, 1989, 2002 and above all, the 70th anniversary of the artist's death. From 1923 to 1977, published works were only protected if the artist first "published" the artwork in the US (i.e. reproduced or publicly displayed it though determining the outer boundaries of the term is a challenge) with a copyright notice and renewed the notice during the year of the 28th anniversary of the first publication. If protected, the copyright term was 95 years from the publication date but as of 1978, protected works created after 1977 are protected for the life of the artist plus 70 years from the date of death (with some exceptions).

The formality of having to renew the copyright notice was abolished in 1992 but that didn't save the works published between 1923 and 1963 whose copyright notice was never renewed. According to a post on The Art Institute of Chicago's blog, "few artists remembered these deadlines and renewed their copyrights." What with the works that were published without notice and those that were but whose notice was never renewed, there must be a substantial number of relatively recent works that do not have copyright protection. It's not possible to summarise the intricacies of US copyright laws here nor am I in a position to do so (I'm not an IP lawyer!) other than to say that 1989 and 2002 also saw fundamental changes being introduced in the area of copyright law and, as before, protection turned on when and where a work was created and published and whether any applicable formalities were satisfied. It goes without saying that none of the above is intended to encourge the art paparrazzi to photograph art nor, I presume, is The New York Times' crucial distinction between violations and enforcement of copyright laws. The point I want to make is that copyright laws in the US are incredibly complicated and as a result, a significant portion of twentieth century art in this country has not been afforded the protection of the law. At least works published after 2002 automatically have copyright protection for the life of the artist plus 70 years from death (the shorter of 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation for works of corporate authorship).

Malborough Gallery sued over allegations that French dealer is selling fake Chinese ceramics

NEW YORK. French art dealer Enrico Navarra is suing Malborough Gallery in federal court for allegedly embarking on a ""systematic campaign" to deny the authenticity of more than 1,200 ceramic plates by famed Chinese artist Chu Teh-Chun and financed by Navarra and his Parisian business." Malborough is purported to have had the artist (aged 90 and currently ailing...) publicly denounce Navarra's plates as fakes. The motive? Money. Malborough had planned to sell a series of 57 vases by Chu for roughly $200,000 each but Navarra's own plans to sell a vast amount of the artist's ceramic plates threatened the gallery's commercial ambitions because it was anticipated that the market would be unable to absorb the increase in supply for these artworks and thus cause the market price to drop. "Meanwhile, Malborough - which has sold about half of its vases - has raised its price for the remainders to $280,000 each." Malborough did not return the New York Post's call for comments.

Thursday, October 07, 2010

Market News

Below are a few links regarding the art market. The second link covers the Lehman Brothers auction in NYC which I had previously decided not to cover in light of the extensive media coverage it received. However, I have included the link below solely because it may say something about which artists the market is currently craving (Chinese art still oh so hot) or, rather more poignantly, which ones it is not (the "atypical 1993 Damien Hirst cabinet" didn't attract a single bid... but nonetheless sold four days later).

- NEW YORK. "Traditional symbols of stability- New England Chippendale furniture, early weathervanes and primitive portraits- struggled to sell at Christie's and Sotheby's Americana sales."

- NEW YORK. Chinese paintings "sold strong," Hirst "drew no bids" and "value deal" on Richard Prince joke painting at Lehman Brothers auction. "It was the sale of unusual suspects," said Gabriela Palmieri, senior specialist in the contemporary art department.

- LONDON. "Medici "loot" for sale?" The perennial problem of provenance and looting in the antiquities market.

- HONG KONG. "$52m Sotheby's Sale of Traditional Chinese Paintings Hits Market's Sweet Pot." Traditional Chinese art has undoubtedly cemented its place as this season's darling. Contrast with the results of Sotheby's modern Chinese art sale.

- HONG KONG. The sale of an Imperial vase for $32.4m topped the auctions of Chinese art in HK this week proving that "Chinese collectors will pay almost anything for what they like."

Labels:

art at auction,

China,

Investing

Tuesday, October 05, 2010

BBC interviews Chairman of Christie's International on the art market and the commercialisation of art

Last night, BBC HARDtalk's Sara Montague spoke with Edward Dolman, former CEO and current Chairman of Christie's International, on the state of the art market, the appeal of art as an alternative investment to stocks or bonds and the growing commercialisation of art. At present, a full version of the interview does not appear to be available online but an extract can be found here. Based on my own notes of the interview, this is what Dolman had to say:

On art as an investment: investors are looking for "tangible assets, especially in a period of inflation" but investors must realize that "the value [of an artwork] can go up and down." Acquiring art for investment purposes is "hardly a new phenomenon" though the principal drivers for an acquisition should be whether the buyer "engages" with and is "inspired" by the artwork.

On the top-end of the art market: a very discrete group of people composed of around "100 to 150" investors/collectors with "the East [referring to Russia, the Middle East and China in particular] playing a much bigger role."

On the recession: the top-end of the art market has recovered but other areas are seeing a "slow recovery."Some pre-recession trends have continued: post-war contemporary and Chinese art are "still hot" and at "the very high end." Dolman went on to discuss the "serious competition" faced by Christie's from the new auction houses in Beijing. However, he said the fact that "most great Chinese works are outside China" gives Western auction houses a competitive advantage over their Chinese counterparts.

On the record-breaking Picasso auctioned last May: people at Christie's were "not surprised" it sold for $106.5m given Picasso is widely considered to be "the greatest artist of the twentieth century" and the place the 1932 painting holds within the artist's oeuvre. Picasso, Dolman said, is "as close to a blue chip investment as you can make in the art market today."

On Christie's as a taste-maker: the auction house is not responsible for "creating tastes" but rather "responds to what clients are wanting to collect" and to demand for certain "categories of styles."

On the tastes that drive the art market today: modernism, "objects that remind them [buyers] of their own time." For example, Warhol "has a huge appeal because he mirrors the society a lot of collectors lived in." Dolman also noted the emergence and development of a "global taste" with Hirst and Koons collectors in Asia becoming some of the most imporant for these artists.

On Christie's' new CEO as a symbol of the commercialisation of art (see here for background): Christie's "is a business after all," a global one with shareholders "who expect returns." The auction house will benefit from the "fresh eyes of an outsider" and the former CEO (who had been at Christie's for 15 years prior to his appointment as CEO in 1999) said the fact that Murphy had no prior experience in the art world was of no importance because people at Christie's "already have a lot of the knowledge."

On any misgivings about the commercialisation of the art world: None. "Society's recognition of the art world is fundamental." The fact that it's "seen as having such great importance explains the value assigned to art."

On Jerry Saltz's view that money corrupts the creative process: such a critique represents "a denial of everything that's happened in the last one hundred years;" patrons are "historically behind great art" and "money and art [have been] linked for generations and generations" (Dolman makes a reference to the Medici). It is "unwise to disconnect money from the livelihood of the artist and his ability to create" and art's "[monetary] value has allowed it to be preserved."

On art as an investment: investors are looking for "tangible assets, especially in a period of inflation" but investors must realize that "the value [of an artwork] can go up and down." Acquiring art for investment purposes is "hardly a new phenomenon" though the principal drivers for an acquisition should be whether the buyer "engages" with and is "inspired" by the artwork.

On the top-end of the art market: a very discrete group of people composed of around "100 to 150" investors/collectors with "the East [referring to Russia, the Middle East and China in particular] playing a much bigger role."

On the recession: the top-end of the art market has recovered but other areas are seeing a "slow recovery."Some pre-recession trends have continued: post-war contemporary and Chinese art are "still hot" and at "the very high end." Dolman went on to discuss the "serious competition" faced by Christie's from the new auction houses in Beijing. However, he said the fact that "most great Chinese works are outside China" gives Western auction houses a competitive advantage over their Chinese counterparts.

On the record-breaking Picasso auctioned last May: people at Christie's were "not surprised" it sold for $106.5m given Picasso is widely considered to be "the greatest artist of the twentieth century" and the place the 1932 painting holds within the artist's oeuvre. Picasso, Dolman said, is "as close to a blue chip investment as you can make in the art market today."

On Christie's as a taste-maker: the auction house is not responsible for "creating tastes" but rather "responds to what clients are wanting to collect" and to demand for certain "categories of styles."

On the tastes that drive the art market today: modernism, "objects that remind them [buyers] of their own time." For example, Warhol "has a huge appeal because he mirrors the society a lot of collectors lived in." Dolman also noted the emergence and development of a "global taste" with Hirst and Koons collectors in Asia becoming some of the most imporant for these artists.

On Christie's' new CEO as a symbol of the commercialisation of art (see here for background): Christie's "is a business after all," a global one with shareholders "who expect returns." The auction house will benefit from the "fresh eyes of an outsider" and the former CEO (who had been at Christie's for 15 years prior to his appointment as CEO in 1999) said the fact that Murphy had no prior experience in the art world was of no importance because people at Christie's "already have a lot of the knowledge."

On any misgivings about the commercialisation of the art world: None. "Society's recognition of the art world is fundamental." The fact that it's "seen as having such great importance explains the value assigned to art."

On Jerry Saltz's view that money corrupts the creative process: such a critique represents "a denial of everything that's happened in the last one hundred years;" patrons are "historically behind great art" and "money and art [have been] linked for generations and generations" (Dolman makes a reference to the Medici). It is "unwise to disconnect money from the livelihood of the artist and his ability to create" and art's "[monetary] value has allowed it to be preserved."

Labels:

art at auction,

Christie's

NY State's version of UPMIFA is "more donor-favorable than perhaps any in the nation"

The New York State statute (the "Act") enacting NY's version of the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act ("UPMIFA") will undoubtedly impact the way not-for-profit institutions manage their endowment funds. The Act makes significant changes to the decades-old New York Not-For-Profit Corporation Law, providing, among other things, that institutions such as museums and universities are no longer required to seek a court order prior to invading the principal of an endowment fund when it is "underwater" (previously there was a bright line rule against doing so without first obtaining court approval). This gives trustees increased flexibility to manage endowment funds though governing boards are "still required to balance historic market performance and the need for current income against inflation, preservation of capital, and a number of other factors." The adoption of the Act also requires that major gifts be given "more attention than in the past and some charities will need to revist their investment strategies for these gifts."

Although not-for-profit institutions generally fall outside the scope of this blog, I nevertheless decided to cover this piece of legislation because several commentators have expresssed concern about how the Act will affect charitable donations, an issue pertinent to many art collectors in New York and elsewhere. Lee Rosenbaum, for example, has said that the new law will encourage "disregard for donor intent." However, according to Nixon Peabody, the Act is "more donor-favorable than perhaps any in the nation" i.e. DC and the 47 other states that have already enacted their own versions of UPMIFA. The Act contains detailed notice requirements under which donors are given special notice prior to "court-ordered and other modifications of restrictions" and charities will need to obtain donor consent to release or modify "certain restrictions in a gift instrument." For more information, click here to read Simpson Thacher's thorough analysis of the Act.

Although not-for-profit institutions generally fall outside the scope of this blog, I nevertheless decided to cover this piece of legislation because several commentators have expresssed concern about how the Act will affect charitable donations, an issue pertinent to many art collectors in New York and elsewhere. Lee Rosenbaum, for example, has said that the new law will encourage "disregard for donor intent." However, according to Nixon Peabody, the Act is "more donor-favorable than perhaps any in the nation" i.e. DC and the 47 other states that have already enacted their own versions of UPMIFA. The Act contains detailed notice requirements under which donors are given special notice prior to "court-ordered and other modifications of restrictions" and charities will need to obtain donor consent to release or modify "certain restrictions in a gift instrument." For more information, click here to read Simpson Thacher's thorough analysis of the Act.

Labels:

charitable donations

Sunday, October 03, 2010

Title insurance "still not broadly accepted"

A New York Times article this weekend on avoiding "legal pitfalls when buying art" (the usual suspects: title and authority to sell an artwork, whether it is subject to I.R.S. liens and/or security interests for unpaid loans and the need for contractual protections) interestingly mentions the market's persistently lukewarm reaction to title insurance. Although hedge funds have shown some interest in purchasing coverage, high-net worth individuals have generally opted not to get insurance. The reason for this seems to be that insurance is not inexpensive (1-5% of the value of the work) and a one-time premium is required to be paid upfront as a lump-sum rather than in installments. Furthermore, coverage is usually limited to title defects and excludes otherwise fraudulent sales.

Donn Zaretsky once referred to "the fundamental weirdness of art title insurance" (insurance traditionally covers future not past events) and the unusual disparity of information between the insured and the insurer. Though I appreciate the legitimate concern regarding the insured's possible exploitation of the insurer, I personally don't think the nature of art title insurance is a major factor accounting for its relative lack of success. In any case, one could interpret the risks covered by title insurance as being future events since breaks in a chain of title technically only become problematic if and when claims are brought in the future against a new owner (and even then, statutes of limitation often bar claims though the bringing of a claim would pose a problem in itself if the buyer wished to resell).

Donn Zaretsky once referred to "the fundamental weirdness of art title insurance" (insurance traditionally covers future not past events) and the unusual disparity of information between the insured and the insurer. Though I appreciate the legitimate concern regarding the insured's possible exploitation of the insurer, I personally don't think the nature of art title insurance is a major factor accounting for its relative lack of success. In any case, one could interpret the risks covered by title insurance as being future events since breaks in a chain of title technically only become problematic if and when claims are brought in the future against a new owner (and even then, statutes of limitation often bar claims though the bringing of a claim would pose a problem in itself if the buyer wished to resell).

The fate of a fake

If you want to know what happens to "fakes" when they're recovered by the FBI or the U.S. Postal Service- the two federal law enforcement agencies that handle most cross-border counterfeit art frauds- click here.

The distortions that result from forgeries being traded in the market are twofold: (i) the historical record is distorted both directly and indirectly by potentially leading to the rejection of the most unusual (and often most informative) artworks for fear of inauthenticity and (ii) the market's price allocation mechanism is distorted by artificially inflating the supply of works by a given artist. These distortions combined with the fact that fakes are notorious for making their way back into the market make it pretty clear that what federal and state law enforcement agencies should do with a recovered fake is "shred it, incinerate it, [or] stamp it so that no one will be fooled again," as Catherine Begley, a former special agent in the New York office of the FBI, said. However, as the article rightly points out, this is not always possible as a result of judicial control over the destruction of counterfeit property (a court order is required) and the overlap between stolen works and fakes (the law generally requires that a stolen artwork, even if fake, be returned to its righful owner).

The distortions that result from forgeries being traded in the market are twofold: (i) the historical record is distorted both directly and indirectly by potentially leading to the rejection of the most unusual (and often most informative) artworks for fear of inauthenticity and (ii) the market's price allocation mechanism is distorted by artificially inflating the supply of works by a given artist. These distortions combined with the fact that fakes are notorious for making their way back into the market make it pretty clear that what federal and state law enforcement agencies should do with a recovered fake is "shred it, incinerate it, [or] stamp it so that no one will be fooled again," as Catherine Begley, a former special agent in the New York office of the FBI, said. However, as the article rightly points out, this is not always possible as a result of judicial control over the destruction of counterfeit property (a court order is required) and the overlap between stolen works and fakes (the law generally requires that a stolen artwork, even if fake, be returned to its righful owner).

Labels:

Authenticity,

counterfeit,

law enforcement

LINKS

PARIS/ LOS ANGELES. Below are a number of links drawing attention to the growing importance of the contemporary art markets in Paris and LA which highlight how the competition between New York and London is slowly being replaced by an increasingly globalised art market (Asia, and Hong Kong in particular, being the other emerging hot spot).

- Sotheby's contemporary art sales in June of this year made "a total of €13.8m, flying past the €7.3-10m estimate." Six months earlier, Sotheby's impressionist and modern art sales had also exceeded high estimates by generating €10.8m.

- Larry Gagosian's ninth gallery will open later this month on the Right Bank with shows of Cy Twombly and Prouvé.

- "I want Paris to be the capital of the art market," says one of France's leading antique dealers.

- "Endowment funds flourish in France."

- Dominique Levy of L&M Arts says they decided to expand the New York-based gallery west to LA rather than to London or Berlin because LA has “a creative energy comparable to what happened in the ‘50s in New York.” See also Artnet's coverage of the gallery's LA opening alongside an account of LACMA's new Renzo Piano pavilion.

- NY Armory Show operator, Merchandise Mart, plans to launch new LA art fair in late 2011.

- MOCA reached deep into the New York art market to find its newest director- Jeffrey Deitch- though not without controversy. Conflicts of interest dictated that Deitch at least divest himself of his commercial commitments (notably the two Lower Manhattan galleries housing Deitch Projects, critically acclaimed for broadening aesthetic horizons) leaving a not insignificant dent in the New York market.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)